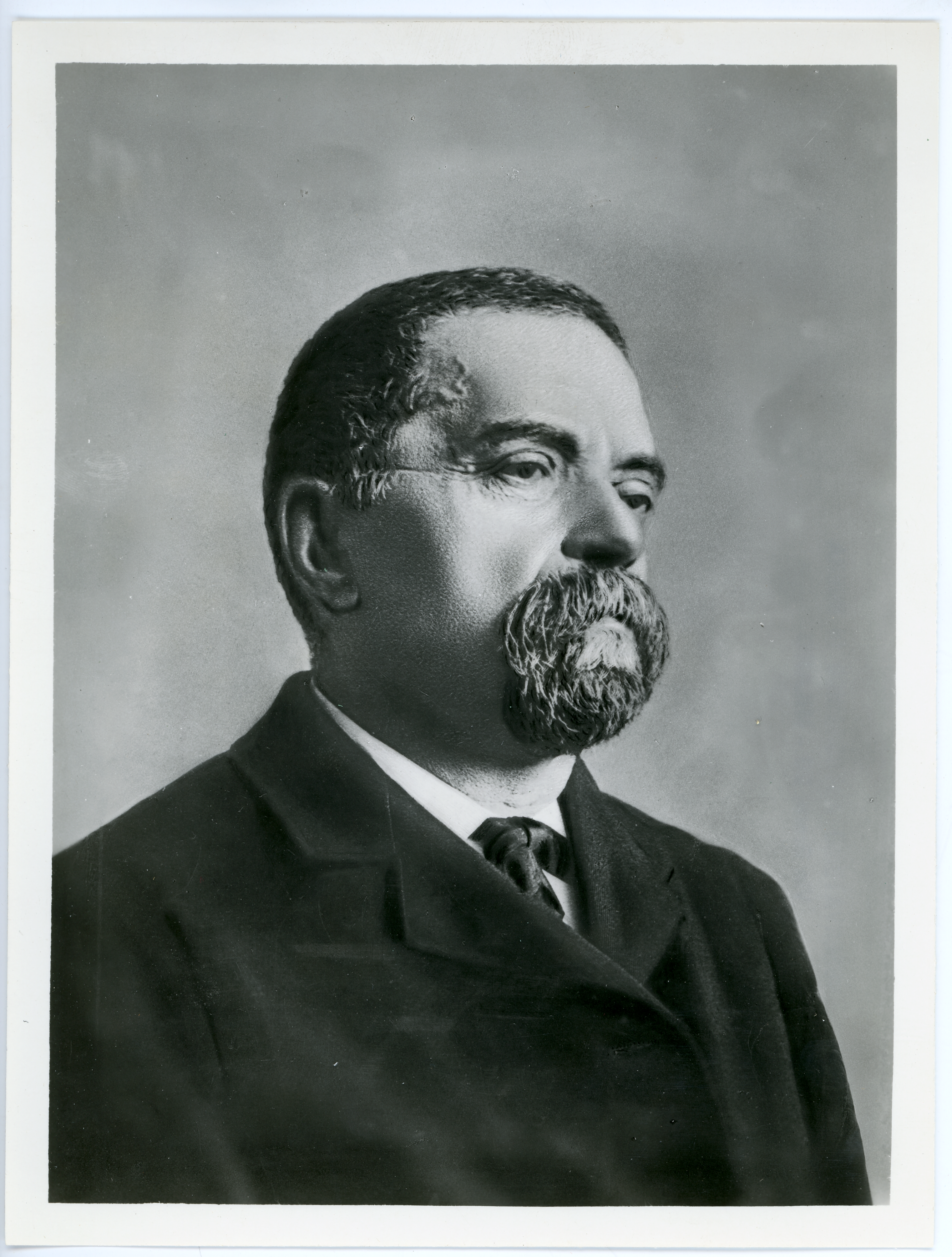

In 1859, following the Armistice of Villafranca, Piedmont annexed Lombardy, as a first step towards the unification of Italy. This political event had immediate consequences on the conditions of the Observatory of Brera: the government of Piedmont, trying to restore the observatory from its state of crisis, due to lack of personnel and scientific instrumentation, sent to Brera Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli (1835–1910) as “second astronomer”. Two years later, in 1862, when the former director Carlini died, Schiaparelli took his place. He was only 27 years old, the youngest director in the entire history of the Observatory.

Schiaparelli was already known as a brilliant scientist, and was also a tireless worker; in short time, with his energy and ingenuity, he gave a new boost to the Observatory. He had graduated at the Polytechnic University of Turin, a city which in that period (from 1861 to 1865) was the capital of Italy, and had the opportunity of meeting some of the most influential political figures of his times. In particular, he got to know Quintino Sella, Finance Minister of the Kingdom of Italy from 1862 to 1873, and Luigi Menabrea, Prime Minister from 1867 to 1869. Quintino Sella strived to obtain for Schiaparelli a scholarship for a study trip across Europe (1857-60), during which he studied in Berlin under the famous astronomer Encke and at Pulkovo Observatory, near Saint Petersburg; Schiaparelli ended his stay there in 1860, when he was appointed as astronomer in Brera.

Thanks to this coincidence of scientific reputation and political contacts he could immediately obtain for the observatory a new telescope; it was ordered in 1862 and arrived in Brera in 1865, but the building of the dome was delayed for several years, so that observations started only in 1875. The new instrument was a refractor built in Germany by Merz firm; its optical quality was very good and allowed precise micrometric measurements. It had an equatorial mount operated by a mechanical drive powered by two heavy weights, like a pendulum clock. The instrument was requested principally for measuring the positions of double stars (systems of two stars orbiting around their center of mass under the action of their mutual gravitational attraction). The observation of those binary systems, extended over timespans of several years or even decades, allows the computation of their orbital parameters and the estimation or their masses; even today this is the most direct method for the measurement of stellar masses. Schiaparelli devoted a substantial fraction of his activity to meticulous observations of binary stellar systems; he retired in 1900, when a gradual deterioration of his eyesight was impeding his work.

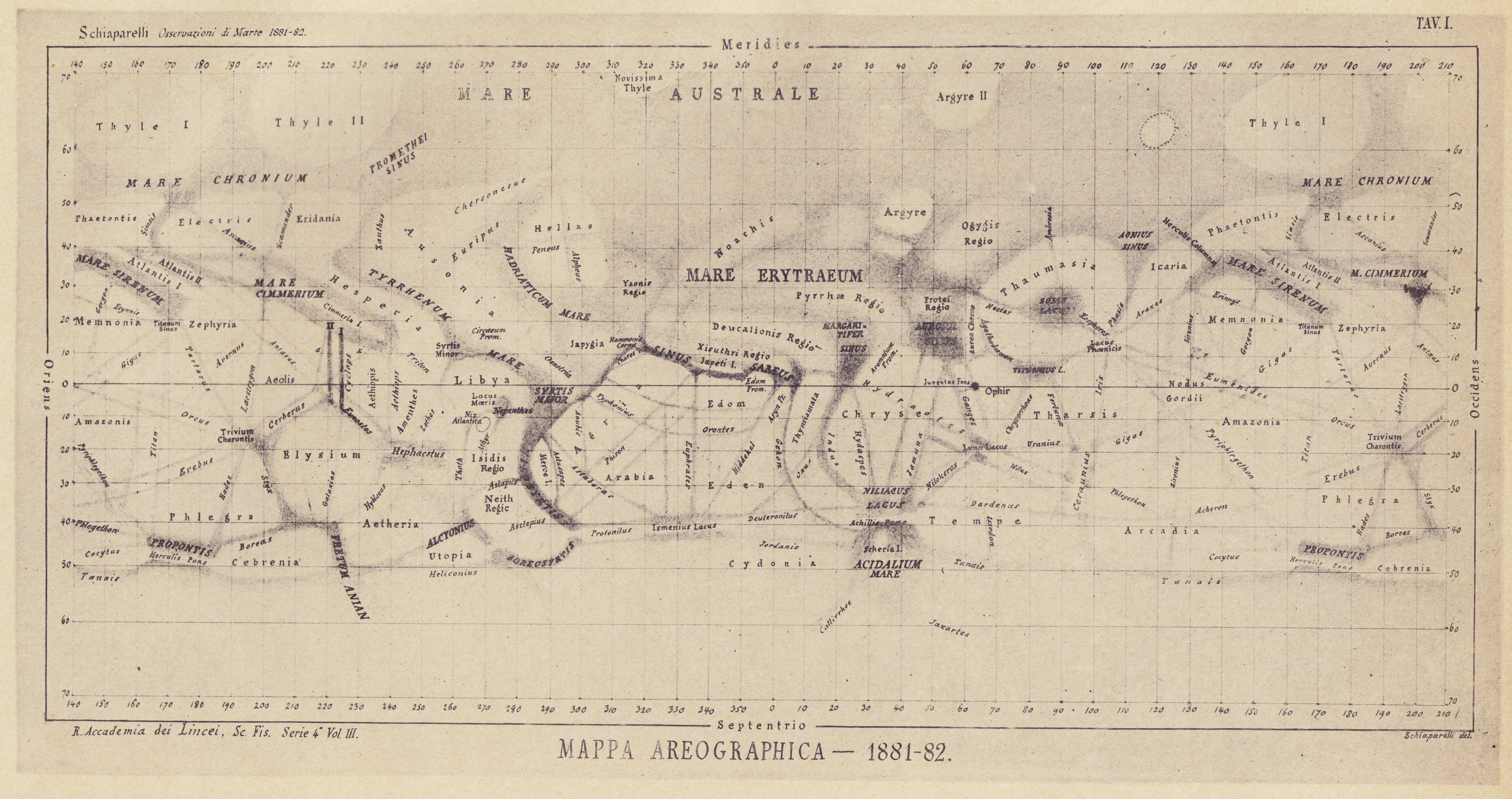

Schiaparelli’s observing activity was extended also to other fields: comets, asteroids, main planets of the Solar System. But Schiaparelli is famous above all for his observations of planet Mars, which he started almost by chance: one night, in which adverse weather conditions prevented him from performing micrometric measurements of double stars, he aimed the telescope towards Mars and realized that, with his new instrument, he could detect on the surface of the planet details which were not displayed in any of the maps available at the time. Therefore he started a survey of Mars topography, observing the planet at every opposition and publishing a series of maps showing increasingly fine details of the surface of the planet. At the time observations were performed only by eye: astronomers spent hours at the ocular of the telescope, trying to make the best from those rare instants in which atmospheric turbulence was lower and allowed a clearer sight of the body they were observing.

In trying to record even the finest details of Mars surface, Schiaparelli was misled by a peculiar kind of optical illusion, caused by the fact that the brain has a tendency to superimpose a definite, geometrical structure on details perceived vaguely and ambiguously by the eye. His maps became crowded with thin, rectilinear markings, which were named “canals”; over time they were showing changes of shape and color, and even appeared as double (a phenomenon called “gemination”). Today we know that those canals do not correspond to any real structure existing on the surface of Mars but at that epoch those observations, considered as genuine representations of Martian topography, raised great interest and heated debates. Schiaparelli has always been very cautious in making assumptions about the real nature of those structures, but other astronomers took much clearer positions, maintaining that the canals were built by an alien civilization dwelling on Mars.

Schiaparelli was the first to demonstrate that meteors (falling stars) originate from comets; having compiled a catalog of the orbits of known comets and collected thousands of observations of falling stars, he showed that the directions from which some of the meteor showers appear to come correspond to the directions of the orbits of some comets, and put forward the hypothesis that meteors are nothing but cometary dust.

In 1880 Schiaparelli obtained financing for acquiring a more powerful telescope. The new instrument (at the time one of the largest in Europe) arrived in Brera in 1882 and was used on a regular basis starting from 1886. It was a refractor, built in cooperation by German factories Merz (for the optical part) and Repsold (for the mount), with a diameter of 18 inches (49 cm) and a focal length of 7 m. To put these events in context, we need to remember that at the epoch the newborn Italian state was facing serious economic hardships, which had compelled to introduce the unpopular tax on flour; that drastic measure had raised violent protests and uprisings, which had been harshly repressed. Nevertheless the Parliament had passed the assignment for the new telescope almost unanimously; in a letter sent to Schiaparelli for informing him about the outcome of the vote, Quintino Sella wrote: «Dear friend, here is the result of the secret ballot. Votes in favor: 192 / Votes against: 37 / Voters: 229. The ballot is really wonderful; in the offices [of the Ministry] and in the House of Representatives they said explicitly that the telescope was granted because there was an astronomer well worth it. The esteem they have for you was very important for the vote. So you can be happy and proud of the solemn appreciation you have been granted by your homeland, unparalleled as far as I remember».