It’s very likely that even the astronomers in Ancient Greece, like Hipparchus of Nicaea, had occasionally noticed Uranus in their skies, because it is visible to the naked eye in excellent seeing conditions, but they thought it was a star. This interpretation held until March 13, 1781, when the astronomer William Herschel, while studying binary star systems, noticed that this “star” had a significant, if slow, proper motion. Due to the immense distance between Earth and any star, with the exception of the Sun, stellar proper motions are in general too slow to be perceived in a few nights or weeks of observation, even though stars are actually moving at thousands of miles per hour. But this wasn’t the case for this object.

Herschel was puzzled by this “fast moving” celestial body and he thought it could be a comet. He started an extensive correspondence with other european astronomers to better interpret his observations. Among them, Francesco Reggio, Angelo De Cesaris e Barnaba Oriani at the Brera Observatory, and Ruggero Boscovich, former director of Brera but by then at the Observatory in Paris. In Paris he was in contact with Messier, a comet seeker who is also famous for his catalogue of nebulae and galaxies (e.g., the Andromeda Galaxy is also known as M31, i.e. object n. 31 in the Messier Catalog).

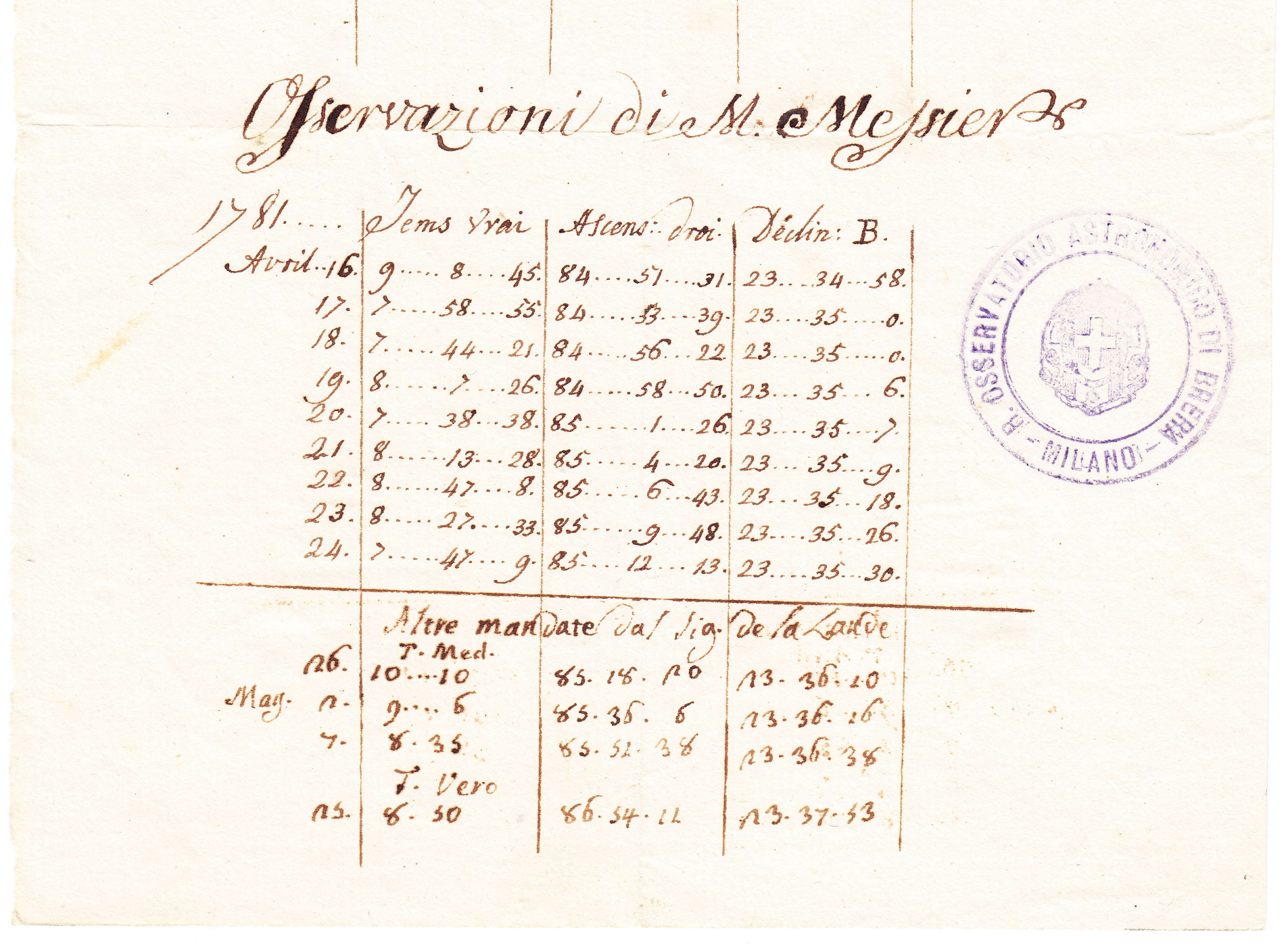

Through a large collaboration and exchange of data between Paris and Brera, Boscovich shared the information he received from Messier with his colleagues in Brera. Was this peculiar object a comet, a planet or was it something of an entirely different nature? Was the orbit parabolic, circular, elliptic? Boscovich himself tried to interpret its nature and determine the orbit. However, it was thanks to Oriani that significant progress on the study of Uranus was made. Oriani used a device called an “Equatorial sector”, a telescope equipped with graduated rings, specially designed to measure angles and positions of celestial bodies. With it, he measured the distance of Uranus from the Sun and its orbital period, after having observed the object every night for a full month.

The final word came from a German astronomer, Johann Bode, who established that the object was a planet and suggest the name Uranus, keeping with the tradition of assigning mythological names to the planets. The Solar System then officially acquired its seventh planet.

Several decades later, when the orbit was determined with much better accuracy, astronomers noticed deviations from the best model that describe the data. The best interpretation was that these were caused by another planet, even more distant from the Sun than Uranus. On September 23, 1846, Neptune was discovered, very close to the location predicted by the astronomers.